|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Página Principal | Universitario | Académico | Recursos | Tendencias | Laboratorios | Formularios | Glosario | Buscador |

||||||||||||||||||

El ser humano re. ca. CONCE Los términos q. Homest ud física, especialmente de los sistemas circulatorio y respiratorios (aeróbicos) (Lopategui, 1997, pp. 32-33). A continuación se discutirán los conceptos relacionados con la salud, bienestar y enfermedad. El Cod Epategui, 1997, p. 3). El Cud Ete. El tar o. EL IAL Ex). CON Eedad. DESCR Evol 96).

Las en10). Una grabla 2). Rel Pue2). Acts. El sehl, 1993). Me Al6-27).

FUENTS DE ENERGÍA PARA EL DEPORTISTA El parad05). EV A travéo. Al presente7). En EL MOES Nuestra. SALU La co

TAPLICACIONES PARA LOS DEPORTES MOVIMIE Consid Se considera quwen, 2008). M El t Al di2011). Act En la a Según estda. Existe la tendencia que la prevalencia de la actividad física para varias culturas disminuye conforme se observa una economía saludable del país (Hardman & Stensel, 2009, p. 14). También, se ha demostrado que se reduce marcadamente los niveles de actividad física según aumenta la edad, donde la población femenina evidencia un menor nivel de actividad física en comparación con los varones (Hardman & Stensel, 2009, p. 14). Ej En 994). APTIT La aptitud física

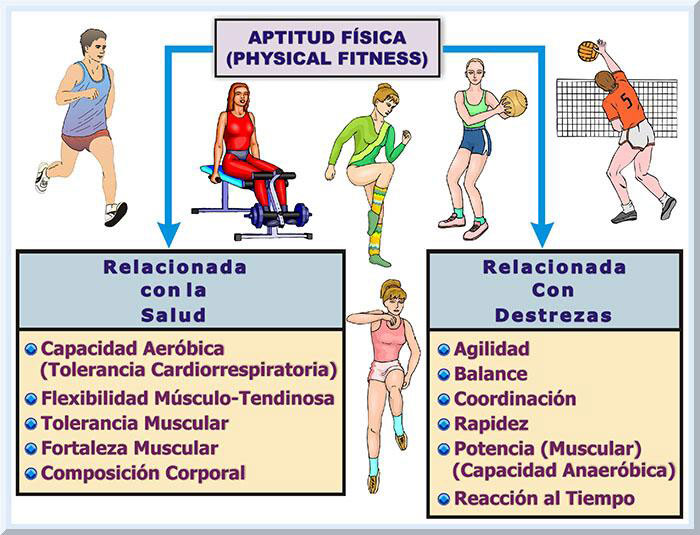

El Co La definición clásica de ap. También, en el 1971, un colectivo de investigadores, pertenecientes a la OMS, expusieron su posición ante el término de aptitud física. Entonces para la OMS, tal concepto representaba "la habilidad para llevar a cabo muscular satisfactoriamente." (Anderson, Shephard, Denolin, Varnauskas & Masironi, 1971). En el 1985 se reveló en la literatura científica una de las publicaciones más citas, en la cual se plantearon los conceptos de actividad física, ejercicio y aptitud física (Casperson, Powel, & Christenson, 1985). Estos autores establecieron que aptitud física representaba "un conjunto de atributos que las personas poseen o alcanzan que se relaciona con la habilidad para llevar a cabo actividad física." Un año mas tarde, Nieman (1986, p. 34) afirmó que la aptitud física era "un estado de energía dinámica y vitalidad que nos capacita/permite no solamente llevar a cabo nuestras tareas diarias, práctica de actividades recreativas y encarar emergencias imprevistas, sino también nos ayuda a prevenir las enfermedades hipocinéticas, mientras se funcione a niveles óptimos de la capacidad intelectual y experimente el disfrute de la vida". En esta misma década, Pate (1988), postuló que tal concepto debería definirse como "un estado caracterizado por (a) una habilidad para realizar actividades diarias con vigor y (b) una demostración de las características y capacidades que están asociadas con un bajo riesgo para el desarrollo de enfermedades hipocinéticas (es decir, aquellas asociadas con inactividad física)." Desde un enfoque cardiorrespiratorio y muscular, Getchell y Anderson (1987, pp. 15-16) afirman que una persona que posea una apropiada aptitud física implica que "el corazón, los vasos sanguíneos, los pulmones y los músculos funcionan al máximo rendimiento." Una de las organizaciones de mayor prestigio internacionalmente, vinculada con la medicina del deporte y ciencias del movimiento humano, es decir, la ACSM, plantearon en el 1990 que la aptitud física significaba "...la habilidad de realizar niveles de moderada a vigorosa actividad física sin fatiga y la capacidad para mantener tal habilidad a lo largo de la vida." (ACSM, 1990). En años recientes, esta organización revisó la definición de aptitud física (Garber, at al. 2011). Otros autores de renombre en el campo de las ciencias del movimiento humano han publicado su postura ante el término aptitud física. Por ejemplo, Miller, Grais, Winslow y Kaminsky (1991) expusieron que el concepto de aptitud física significaba un "un estado de habilidad para realizar un trabajo físico sostenido caracterizado por una integración efectiva de la tolerancia cardiorrespiratoria, fortaleza muscular, flexibilidad, coordinación y composición corporal". Por su parte, Howley y Franks (2007, p. 517), fundamentado en el planteamiento de Casperson, Powel, y Christenson, (1985) proponen que la aptitud física es un agregado de particularidades únicas, lo cual facilita al individuo ejecutar efectivamente actividades físicas. En otro orden, Lopategui (2006, p. 44) intentó reconceptualizar la definición tradicional de aptitud física, indicando que "...representa la habilidad que posee la persona para llevar a cabo todo tipo de trabajo físico efectivamente y sin fatiga excesiva, particularmente actividades que demandan capacidades cardiorrespiratorias, de las cuales el individuo se recupera con prontitud para ejecutar otras tareas físicas (cotidianas, deportes recreativos) o manejar situaciones de emergencias que pudieran requerir un esfuerzo físico." Tal enfoque retoma elementos que constituyen parte de la primera definición de aptitud física (President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports,1971). A esta definición, se puede integrar la importancia de un óptimo nivel de aptitud física (elevado estado de energía y vitalidad) para la prevención de enfermedades crónicas-degenerativas que emergen principalmente a raíz de un comportamiento sedentario (Nieman,2007, p. 779) (véase Gráfico 14).

Los Componentes de la Aptitud Física

Componentes Relacionados con la

Salud

EL ENFOQUE TERAPÉUTICO MODERNO EN LOS

CAMPOS DE LAS CIENCIAS

MÉDICAS Y LA SALUD: El movimiento es una necesidad en los seres humanos y, a consecuencia de satisfacer esa exigencia, han surgido guías enfocadas a incrementar la participación de la población en actividades físicas, ejercicios, deportes, juegos y recreación (Rahl, 2010, pp. 15-41). En la mayoría de los casos, las intervenciones clínicas que emplean el movimiento humano (ejercicio, actividad física), han mostrado un significante beneficio al paciente con este enfoque terapéutico (Painter, 2008). La incorporación de programas de ejercicio, actividad física y deportes en pacientes con enfermedades crónicas resulta en una variedad de beneficios morfofuncionales y psicológicos, como lo son el mejoramiento de la toleracia cardiorrespiratoria y muscular, la fortaleza muscular, la movilidad articular, la coordinación motora, confidencia y la auto-estima (Young, 1987, p. 20). Tradicionalmente, la medicina se concentra en el tratamiento convencional para una variedad de enfermedades. Este sistema terapéutico se ha transformado a través de las épocas, donde se incorpora la medicina alternativa, como lo son las intervenciones del ejercicio y la actividad física. Además, la práctica de los profesionales de la salud de hoy día enfatiza la prevención primaria de patologías degenerativas y el entrenamiento integrado o funcional. Ésta última iniciativa pretende preparar, a niveles óptimos, las aptitudes físicas y fisiológicas del organismo humano, de manera que realicen efectivamenta las tareas físicas cotidianas, ocupacionales y recreativas. APTITUD FÍSICA FUNCIONAL A través de las décadas, los problemas de salud se han tratado mediante intervenciones médicas convencionales, tales como la terapéutica farmacológica y quirúrgica. Recientemente, se ha evidenciado un auge por la medicina alterna, particularmente en el uso del movimiento para tratar diversos males del ser humano. Sabemos que el ejercicio posee muchos beneficios para la población general y que puede ayudar en la rehabilitación de un gran número de enfermedades incapacitantes. Una ventaja, de suma importancia, que disponen los ejercicios físicos es que ayudan a los participantes ha ser más independientes, durante sus actividades físicas cotidianas, al mejorar la aptitud física funcional (o función física) del individuo aparentemente saludable (Brill, 2004, pp. 3-8; Garber, Blissmer, Deschenes, Franklin, Lamonte, Lee, Nieman, & Swain, 2011; Page, 2005; Sipe & Ritchie, 2012; Weiss, Kreitinger, Wilde, Wiora, Steege, Dalleck & Janot, 2010) y aquellos con disfunciones de la salud (Prakash, Hariohm, Vijayakumar & Bindiya, 2012). Por consiguiente, el enfoque de los programas de ejercicios y actividad física pueden ser de tipo preventivo o terapéutico, pero siempre enfatizando en la importancia de una adecuada aptitud física funcional y óptima calidad de vida. EL EJERCICIO ES MEDICINA® En años recientes, existe una tendencia para que los médicos empleen el ejercicio como una alternativa muy útil para el tratamiento de la gran gama de enfermedades que padece la población humana. Esta iniciativa fue impulsada por el Colegio Americano de Medicina del Deporte (American College of Sports Medicine, con sus siglas ACSM), conocido con el nombre de Exercise is Medicine™ (ACSM, 2008; Durstine, Peel, LaMonte, Keteyian, Fletcher, & Moore, 2009, pp. 21-30; Moore, Roberts, & Durstine, 2009, p.4; Jonas & Phillips, 2009). El movimiento de Exercise is Medicine™ (El Ejercicio es Medicina®) representa una iniciativa transdisciplinaria dirigida a fomentar la actividad física y el ejercicio en un ámbito clínico. Entonces, el propósito de tal iniciativa es integrar el movimiento humano en los sistemas preventivo y terapéuticos de la medicina. El enfoque de Exercise is Medicine™ involucra una comunidad internacional, buscando incorporar esta iniciativa en la mayor cantidad de paises posibles. Diversos profesionales aliados a la salud (Ej: fisiólogos del ejercicio, nutricionistas, terapistas físicos, enfermeras(os), educadores de salud, educadores físicos y otros), así como proveedores para el cuidado de la salud, son parte del equipo que promueve este esfuerzo, de naturaleza global. Se trata, pues, de integrar las ciencias del movimiento humano en el sistema médico, así como en una variedad de instituciones y comunidades. Por ejemplo, tales cedes del programa de Exercise is Medicine™ puede incluir a Universidades, centros comunales de urbanizaciones, hospitales, centros de cuidado para envejecientes, hospitales pediátricos y otros. Como fue mencionado previamente, uno de los objetivos de Exercise is Medicine™ es que parte de la práctica clínica de los médicos incorpore a la actividad física y el ejercicio dentro de los posibles medios para tratar las enfermedades crónicas, infecto-contagiosas, los problemas mentales, así como otras patologías. FISIOLOGÍA DEL EJERCICIO CLÍNICO Para poder llevar a cabo estos esfuerzos preventivos y terapéuticos del movimiento humano es necesario estar preparado en la fisiología del ejercicio clínico (Ehrman, Gordon, Visich, & Keteyian, 2009). La fisiología del ejercicio clínico se encarga de indagar en cuanto al vínculo existente entre el ejercicio y las enfermedades crónicas. En tal campo, de las ciencias del movimiento humano, se estudian los efectos agudos y crónicos del ejercicio en pacientes que poseen patologías incapacitantes. Además, se establecen los protocolos a seguir para realizar diversas pruebas de ejercicio, así como la prescripción de ejercicio en esta población enferma. La definición de un fisiólogo del ejercicio clínico varía según sea la organización encargada de certificarlo, como lo son la ACSM, American Society of Exercise Physiologist (ASEP), American Council on Exercise (ACE) y la Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology (CSEP). Un capítulo de la ACSM es la Asociación de Fisiólogos del Ejercicio Clínicos (Clinical Exercise Physiology Association o CEPA, siglas en ingles). EL MOVIMIENTO DE PERSONAS SALUDABLES La iniciativa de Personas Saludables (Healthy People) representa un esfuerzo nacional para la promoción de la salud y la prevención de enfermedades. En el mismo de formulan una serie de objetivos y metas que se esperan lograr dentro de un periodo de 10 años. Este trabajo se conceptualizó en el 1979 por medio del documento conocido con el nombre: Healthy People: The Surgeon General's Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (USDHHS, 1979). Tal publicación tenía como meta asistir en las acciones de prevención para las enfermedades crónico-degenerativas, particularmente aquellos problemas de salud que representan las primeras causas de muerte en los Estados Unidos Continentales. Esta problemática es común en muchos países, como lo son Puerto Rico y otros. Algunas de estas patologías degenerativas mortales son, a saber: las enfermedades del corazón, cáncer, enfermedades cerebrovasculares, enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica, diabetes sacarina (mellitus), entre otras. Hoy día, tales trastornos degenerativos forman parte del perfil epidemiológico para las principales causas de mortalidad en Puerto Rico y Estados Unidos Continentales. A raíz de este proyecto federal, en el 1980 se desarrollaron los primeros objetivos de salud nacionales en el documento titulado: Promoting Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives for the Nation (USDHHS, 1980). En este trabajo, se establecieron 226 objetivos de salud (con 15 áreas medulares), enfocándose prospectivamente para el año 1990. En el informe se planteó que las metas principales para el año de 1990 fue: 1) reducir la tasa de mortalidad en la población pediátrica y adulta y 2) aumentar la aptitud física funcional para el colectivo de adultos envejecientes. La publicación: Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives, fue generada en el 1990, exponiendo un listado de 312 objetivos de salud, los cuales fueron divididos en 22 áreas medulares (USDHHS, 1991). Concentrándose para el año 2000, se establecieron tres metas medulares, que fueron: 1) aumentar la expectativa de vida al nacer, 2) disminuir las disparidades de salud y 3) disponibilidad para el acceso de servicios preventivos para toda la población. En este documento, se redactaron 13 objetivos vinculados con la actividad física y aptitud física. De este grupo de objetivos, uno fue cumplido, que fue el relacionado con el incremento de programas de aptitud física en los escenarios ocupacionales (USDHHS, CDC & NCHS, 2001). En el 2000 se presentó otro conjunto de objetivos de salud a nivel nacional, nos referimos a la publicación conocida como: Healthy People 2010 (USDHHS, 2000). En este documento se establecieron 467 objetivos específicos de salud y 28 áreas medulares. Las metas correspondientes fueron: 1) aumentar la expectativa de vida al nacer dentro de un espectro de una vida saludable y 2) erradicar las disparidades de salud. Al presente, se encuentran vigente los objetivos nacionales dirigidos hacia el año 2020, es decir: Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2010). En este documento, los objetivos específicos de salud aumentaron a 580, donde se ubican 39 áreas medulares. Se espera que para el 2020: 1) se alcance una alta calidad de vida y expectativa de vida al nacer, libre de enfermedades preventivas; 2) lograr una equidad tocante a la salud, donde se eliminen disparidades; 3) el desarrollo de ambientes ecológicos que fomenten niveles apropiados de salud; 4) estimular la calidad de vida, el desarrollo saludable y comportamiento saludables a lo largo de las etapas de la vida (USDHHS, s.f; Wright, 2012). PROGRAMAS DE SALUD Y APTITUD FÍSICA CORPORATIVA El movimiento de los programas de salud y aptitud física para los escenarios ocupacionales y comunitarios comenzó desde la década de los 70 (Whitmer, 2009). Parte de tal surgir, por las estrategias de ejercicios y salud en las compañías, se debió a la disponibilidad de investigaciones científicas que evidenciaban los beneficios a nivel de los empleados y para la salud económica de la corporación. Algunos de estas ventajas son: 1) disminución en los costos médicos, 2) incremento en el nivel de productividad de los empleados, 3) disminución en la tasa de ausentismo, 4) menor rotación de los empleados y 4) mayor capacidad para reclutar y mantener en el empleo de trabajadores de alta efectividad productiva (Fabius & Frazee, 2009). Beneficios de un Programa de Aptitud Física Corporativa Los programas de salud y aptitud física concentrados en los empleados de una compañía, poseen el potencial de: 1) mejorar la salud individual de los trabajadores y asistir en la prevención de enfermedades crónico-degenerativas; 2) puede fomentar un mejor ambiente psicosocial en el escenario ocupacional, 3) aportan al logro de la misión, así como sus metas a corto y largo plazo de la organización, como lo puede ser la reducción en el ausentismo y aumento en la productividad; 4) acortar los costos del servicio médico que disponen los empleados, lo cual previene una posible inflación; 5) ayudan a mejorar el estado general de la industria (Patton, Corry, Gettman & Graf, 1986, p. 21). Las compañía tienen mucho que ganar si implementan estos programas de salud y aptitud física. Se han establecido diversos beneficios de naturaleza costo-efectivos, como lo son, a saber: 1) mejor estado del bienestar de la mayoría de los empleados involucrados en el programa; 2) incremento en la moral de los trabajadores; 3) disminuye la partida para los costos asignados a los planes médicos de la industria; 4) los trabajadores se ausentan con menos frecuencia; 5) la productividad de la corporación aumenta; 6) menor incidencia de accidentes laborales; 7) los trabajadores reciben una educación más efectiva concerniente a controversias en el campo de la salud; 8) disminuyen las reclamaciones por compensación en el trabajo (USDHHS, 1993). American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology

[ACOG] Committee Obstetric Practice (2002). ACOG Committee opinion. Number 267,

January 2002: exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

Obstetrics Gynecology, 99(1), 171-173. Ainsworth, B. E., Haskell, W. L., Whitt, M. C., Irwin, M. L., Swartz, A. M., Strath, S. J., O'Brien, W. L., Bassett, D. R. Jr, Schmitz, K. H., Emplaincourt, P. O., Jacobs, D. R. Jr, & Leon, A. S. (2000). Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 32(9 Suppl), S498-S504. Recuperado de http://juststand.org/portals/3/literature/compendium-of-physical-activities.pdf Aballay, L., Eynard, A., Pilar, Navarro, A., & Muñoz, S. (2013). Overweight and obesity: a review of their relationship to metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and cancer in South America. Nutrition Reviews, 71(3), 168-179. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00533.x Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (CINAHL with Full Text). Alberti, K. G., Zimmet, P., & Shaw, J. (2006). Metabolic syndrome–a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabetic Medicine, 23(5), 469–480. Recuperado de http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01858.x/pdf Alberti, K. G., & Zimmet, P. Z. (1998).

Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its

complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus

provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabetic Medicine, 15(7),

539–553. Recuperado de

http://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/philip.home/who_dmg.pdf American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation [AACVPR] (2004a). Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention Programs (4ta. ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. 280 pp. American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] (2010). ACSM's Health-Related Physical Fitness Assessment Manual (3ra. ed., pp. 2, 16). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

American College of Sports

Medicine [ACSM] (2008). Exercise is Medicine™. Action and

Promotion Guide. Recuperado de

American College of Sports

Medicine [ACSM] (2008). Exercise is Medicine™. Your

Prescription for Health Series: Information and

recommendations for exercising safely with a variety of

health conditions.

Recuperado de http://exerciseismedicine.org/documents/YPH_Series.pdf American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] (2006). ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (7ma. ed., pp, 135, 141). Baltimore: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins. American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] (2010). ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (8va. ed., pp., 166-167, 207-224). Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins. American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] (2014a). ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (9na. ed., pp. 19-36, 40-57, 162-180). Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins. American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] (2014b). ACSM's Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (7ma. ed., pp. 170-177, 324-330, 337, 424, 466-479). Philadelphia, PA: Lipincott Williams & Wilkins. American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] (1990). The recommended quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness in healthy adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 22(2), 265-274. American Diabetes Association [ADA] (2013). Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care, 36(1), S67-S74. Recuperado de http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/36/Supplement_1/S67.full.pdf+html American Heart Association [AHA], &

American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] (1998). AHA/ACSM Joint Position

Statement: Recommendations for Cardiovascular Screening, Staffing, and Emergency

Policies at Health/Fitness Facilities. Medicine & Science in Sports &

Exercise, 30(6), 1009-1018. Anderson, K. L., Shephard, R. J., Denolin, H., Varnauskas, E., & Masironi, R. (1971). Fundamental Exercise Testing. Geneva: World Health Organization. 133 pp. Andersen, R. E., Crespo, C. J., Bartlett, S. J., Cheskin, L. J., & Pratt, M. (1998). Relationship of physical activity and television watching with body weight and level of fatness among children: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 279(12), 938-942. Recuperado de http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=187368 Aston, G. (2013). Diabetes: An alarming epidemic. Hospitals & Health Networks, 87(2), 34-38. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (CINAHL with Full Text). Australian Bureau of Statistics: How Australians Use Their Time. Canberra, Australia, Commonwealth of Australia, 2006.

Balady, G. J., Chaitman, B., Driscoll, D., Foster, C., Froelicher, E., Gordon,

N., Pate, R, Rippe, J., & Bazzarre, T. (1998). Recommendations for

Cardiovascular Screening, Staffing, Bankoski, A., Harris, T. B., McClain, J. J., Brychta, R. J., Caserotti, P., Chen, K. Y., Berrigan, D., Troiano, R. P., & Koster, A. (2011). Sedentary activity associated with metabolic syndrome independent of physical activity. Diabetes Care, 34(2), 497–503. doi:10.2337/dc10-0987. Recuperado de http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3024375/pdf/497.pdf Bassett, D. R. Jr, Freedson, P., &

Kozey, S. (2010). Medical hazards of prolonged sitting [Versión electrónica]. En

R. M. Enoka, (Ed.), Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews: Vol. 38, Issue 3

(pp. 101-102). Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. doi:

10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373ee. Recuperado de Bauman, A. (2007). Physical activity and exercise progrmash. En C. Bouchard, S. N. Blair, & W. L. Haskell (Eds.), Physical Activity and Health (pp. 319-334). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Bauman, W. A., Spungen, A. M. (2008). Coronary heart disease in individuals with spinal cord injury: assessment of risk factors. Spinal Cord, 46(7), 466-476. doi:10.1038/sj.sc.3102161. Recuperado de http://www.nature.com/sc/journal/v46/n7/pdf/3102161a.pdf Benjamin, E. J., Larson, M. G., Keyes, M. J., Mitchell, G. F., Vasan, R. S., Keaney, J. F. Jr., Lehman, B. T., Fan, S., Osypiuk, E., & Vita, J. A. (2004). Clinical correlates and heritability of flow-mediated dilation in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 109(5), 613-619. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112565.60887.1E. Recuperado de http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/109/5/613.full.pdf+html Berg, J. M., Tymoczko, J. L., Stryer, L., &

Gatto, G. J. (2012). Biochemistry (7ma. ed., p. 773). New York: W.

H. Freeman and Company. Bey, L., Akunuri1, N., Zhao, P.,

Hoffman, E. P., Hamilton, D. G., & Hamilton, M. T. (2003). Patterns of global

gene expression in rat skeletal muscle during unloading and low-intensity

ambulatory activity. Physiological Genomics, 13, 157–167.

doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00001.2002. Recuperado de

http://physiolgenomics.physiology.org/content/13/2/157.full.pdf+html Bhopal, R. S. (2002). Concepts of Epidemiology: An Integrated Introduction to the Ideas, Theories, Principles, and Methods of Epidemiology (pp. p. xxi-xxii, 2-4, 17-18). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost: eBook Collection Bjorvatn, B., Sagen, I. M., Øyane, N., Waage,

S., Fetveit, A., Pallesen, S., & Ursin, R. (2007). The association between sleep

duration, body mass index and metabolic measures in the Hordaland Health Study.

Journal of Sleep Research, 16(1), 66-76. doi:

10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00569.x. Blair, S. N., & Connelly, J. C. (1996). How much physical activity should we do? The case for moderate amounts and intensities of physical activity. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 67(2), 193-205. Blair, S. N., Kampert, J. B., Kohl III, H. W., Barlow, C. E., Macera, C.A., Paffenberger, Jr., R. S., & Gibbons, L. W. (1996). Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. Journal of the American Association, 276(3), 205-210. Blanchet, M. (1990). Assessment of health status. En C. Bouchard, R. J. Shephard, T. Stephens, J. R. Sutton, & B. D. Mcpherson (Eds.), Exercise fitness, and health: A consensus of current knowledge (pp. 127-131). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc. Bompa, T. O. (199). Periodization training for sports (pp. 32-42). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.. Bouchard, C., Blair, S. N., & Haskell, W. (2007). Why study physical activity and health?. En C. Bouchard, S. N. Blair, & W. L. Haskell (Eds.), Physical Activity and Health (pp. 3-19). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Bouchard, R. J. Shephard, T. Stephens, J. R. Sutton, & B. D. Mcpherson (1990). Exercise, fitness, and health: The consensus statement. En C. Bouchard, R. J. Shephard, T. Stephens, J. R. Sutton, & B. D. Mcpherson (Eds.), Exercise fitness, and health: A consensus of current knowledge (pp. 3-28). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc. Boutcher, Y. N., & Boutcher, S. H. (2005). Limb vasodilatory capacity and venous capacitance of trained runners and untrained males. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 95(1), 83-87. Bowman, S. A. (2006).Television-viewing characteristics of adults: correlations to eating practices and overweight and health status. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3(2), A38. Recuperado de http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/apr/pdf/05_0139.pdf Breslow, L. (1990). Lifestyle, Fitness, and Health. En C. Bouchard, R. J. Shephard, T. Stephens, J. R. Sutton, & B. D. Mcpherson (Eds.), Exercise fitness, and health: A Consensus of current knowledge (pp. 155-163). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc. Brill, P. A. (2004). Functional fitness for older adults (pp. 3-8). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Byrd-Bredbenner, B., & Grasso, D. (1999). Prime-time health: An analysis of health content in television commercials broadcast during programs viewed heavily by children. The International Electronic Journal of Health Education, 2(4), 159-169. Recuperado de http://www.aahperd.org/aahe/publications/iejhe/upload/99_C_byrd.pdf

Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology [CSEP] (2013). The Physical Activity

Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q). Recuperado de

http://www.csep.ca/cmfiles/publications/parq/par-q.pdf Caroll, L. W. (1998). Understanding chronic illness from the patient's perspective. Radiologic Technology, 70(1), 37-41. Centro de Salud Deportiva y Ciencias del Ejercicio [SADCE] (1988). Niveles de descripción del comportamiento. En Center for Sports Health and Exercise Science. Puerto Rico, Salinas: Albergue OlImpico y Comité Olímpico de Puerto Rico. Ching, P. L., Willett, W. C., Rimm, E. B., Colditz, G. A., Gortmaker, S. L., & Stampfer, M. J. (1996). Activity level and risk of overweight in male health professionals. American Journal of Public Health, 86(1), 25-30. Recuperado de http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1380355/pdf/amjph00512-0027.pdf Chiras, D. D. (1999). Human Biology: Health, Homeostasis, and the Environment (3ra. ed., pp. 4-7). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. Clinical Exercise Physiology

Association [CEPA]. CEPA is a member of the ACSM Afiliate Societies. Recuperado

de Cornett, S. J., & Watson, J. E. (1984). Cardiac rehabilitation: An interdisciplinary team approach (pp. 2-3). New York: John Wiley & Sons. Corbin, C. B., & Lindsey, R. (1997). Concepts of fitness and wellness: With laboratories (2da. ed., p. 5, 25-27). Madison, WI: Brown & Benchmarl Publishers. Cornier, M. A., Dabelea, D., Hernandez, T. L., Lindstrom, R. C., Steig, A. J., Stob, N. R., Van Pelt, R. E., Wang, H., & Eckel, R. H. (2008). The metabolic syndrome. Endocrine Reviews, 29(7), 777-822. doi:10.1210/er.2008-0024. Recuperado de http://edrv.endojournals.org/content/29/7/777.full.pdf+html De Cocker, K. A., De Bourdeaudhuij, I. M., Brown, W. J., & Cardon, G. (2008). The effect of a pedometer-based physical activity intervention on sitting time. Preventive Medicine, 47(2), 179-181. Demiot, C., Dignat-George, F., Fortrat, J. O., Sabatier, F., Gharib, C., Larina, I., Gauquelin-Koch, G., Hughson, R., & Custaud, M. A. (2005). WISE 2005: chronic bed rest impairs microcirculatory endothelium in women. American Journal of Physiology Heart and Circulation Physiology, 293(5), H3159-H3164. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00591.2007. Recuperado de http://ajpheart.physiology.org/content/293/5/H3159.full.pdf+html Departamento de Salud, Secretaría Auxiliar de Planificación y Desarrollo (2004). Informe Anual de Estadísticas Vitales 2003 (pp. 111-118, 141, 227-228). San Juan, Puerto Rico: ELA, Departamento de Salud. Recuperado de http://www.estadisticas.gobierno.pr/iepr/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=7ADJ6fSujrM=&tabid=186. de Pontes, L., M, dos Santos Pinheiro, S., Monteiro, Zemolin, C, Carvalho de Araújo, da Silva, R. L., Duarte, Kumamoto, F., Í., & Sandoval Vilches, Á. E. (2008), Standard of physical activity and influence of sedentarism in the occurrence of dyslipidemias in adult. Fitness & Performance Journal, 7(4), 245-250. doi:10.3900/fpj.7.4.245.e. Recuperado de http://www.fpjournal.org.br/painel/arquivos/951-6DislipidemiasemadultosRev42008Ingles.pdf DeSimone, G., & Stenger, L. (2012). Profile of a group exercise participant: health screening tools. En G. DeSimone (Ed.), ACSM's Resources for the group exercise instructor (pp. 10-33). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. De Vattuone, L. F., & Graig, M. L. (1985). Educación para la Salud (11ma. ed.; pp. 1-2, 7-11, 41-46, 258-259). Buenos Aires: Librería "El Ateneo" Editorial. Dietz, W. H. Jr., & S. L. Gortmaker (1985). Do we fatten our children at the television set? Obesity and television viewing in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 75(5), 807-812. Recuperado de http://corcom130-sp10-advertising.wikispaces.umb.edu/file/view/Pediatrics+May+1985.pdf Dishman, R. K., Washburn, R. A., & Health, G. W. (2004). Physical activity epidemiology (pp. 13-14, 443, 447). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, Inc. Donahoo, W. T., Levine, J. A., & Melanson, E. L. (2004). Variability in energy expenditure and its components. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care, 7(6), 599-605. Donatell, R., Snow, C., & Wilcox, A. (1999). Wellness: Choices for Health and Fitness (2da. ed., p.7). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company. Dunstan, D.W., Barr, E. L., Healy, G. N., Salmon, J., Shaw, J. E., Balkau, B., Magliano, D. J., Cameron, A. J., Zimmet, P. Z., & Owen, N. (2010). Television viewing time and mortality: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Circulation, 121(3), 384-391. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894824. Recuperado de http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/121/3/384.full.pdf+html Dunstan, D. W., Healy, G. N., Sugiyama, T., &

Owen, N. (2010). ‘Too much sitting’ and metabolic risk – Has modern technology

caught up with us? European Endocrinology, 6(1), 19-23. Recuperado

de

http://www.touchendocrinology.com/articles/too-much-sitting-and-metabolic-risk-has-modern-technology-caught-us?page=0,0

Dunstan, D. W., Salmon, J., Healy, G. N., Shaw, J. E., Jolley, D., Zimmet, P. Z., & Owen N. (2007). Association of television viewing with fasting and 2-h postchallenge plasma glucose levels in adults without diagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Care, 30(3), 516-522. Recuperado de http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/30/3/516.full.pdf+html Dunstan, D. W., Salmon, J., Owen, N., Armstrong, T., Zimmet, P. Z., Welborn, T. A., Cameron, A. J., Dwyer, T., Jolley, D., & Shaw, J. E.(2005). Associations of TV viewing and physical activity with the metabolic syndrome in Australian adults. Diabetologia, 48(11), 2254-2261. Dunstan, D. W., Salmon, J., Owen, N., Armstrong, T., Zimmet, P. Z., Welborn, T. A., Cameron, A. J., Dwyer, T., Jolley, D., & Shaw, J. E. (2004). Physical activity and television viewing in relation to risk of undiagnosed abnormal glucose metabolism in adults. Diabetes Care, 27(11), 2603-2609. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.11.2603. Recuperado de http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/27/11/2603.full.pdf+html Durstine, J. L., Moore, G. E.,

Painter, P. L., & Roberts, S. O. (Eds.). (2009). ACSM's Exercise

Management for Persons with Chronic Diseases and Disabilities Durstine, J. L., Peel, J. B., LaMonte, M. J., Keteyian, S. J., Fletcher, E., & Moore, G. E. (2009). Exercise is medicine. En J. L. Durstine, G. E. Moore, P. L. Painter, & S. O. Roberts (Eds.), ACSM's exercise management for persons with chronic diseases and disabilities (3ra. ed., pp. 21-30). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, Inc. Edwardson, C. L., Gorely, T.,

Davies, M. J., Gray, L. J., Khunti, K., Wilmot, E. G., Yates, T., & Biddle, S.

H. (2012). Association of Sedentary Behaviour with Metabolic Syndrome: A

Meta-Analysis. Plos ONE, 7(4), 1-5.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034916. Recuperado de Ehrman, J. K., Gordon, P. M., Visich, P. S., & Ketteyian, S. J. (2009). Introduction. En J. K. Ehrman, P. M. Gordon, P. S. Visich & S. J. Ketteyian (Eds.), Clinical exercise physiology (2da. ed., pp. 3-15). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Ekelund, L. G., Haskell, W. L., Johnson, J. L., Whaley, F. S., Criqui, M. H., & Sheps, D. S. (1988). Physical fitness as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in asymptomatic North American men. The Lipid Reasearch Clinics Mortality Follow-up Study. The New England Journal of Medicine, 319(21), 1379-1384. Recuperado de http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/328/8/533. Epstein, L. H., Valoski, A. M., Vara, L. S., McCurley, J., Wisniewski, L., Kalarchian, M. A., Klein, K. R., & Shrager, L. R., (1995). Effects of decreasing sedentary behavior and increasing activity on weight change in obese children. Health Psychology, 14(2), 109-115. Fabius, R. J., & Frazee, S. G. (2009). Workplace-based health and wellness services. En N. P. Pronk (Ed.), ACSM’s worksite health handbook: A guide to building healthy and productive companies (2da.ed., 21-30). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Faith, M., Berman, N., Heo, M., Pietrobelli, A., Gallagher, D., Epstein, L., Eiden, M. T., & Allison, D. (2001). Effects of contingent television on physical activity and television viewing in obese children. Pediatrics, 107(5), 1043-1048. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (Academic Search Premier). Fan, J., Unoki, H., Kojima, N., Sun, H., Shimoyamada, H., Deng, H., Okazaki, M., Shikama, H., Yamada, N., & Watanabe, T. (2001). Overexpression of lipoprotein lipase in transgenic rabbits inhibits diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276(43), 40071-40079. Recuperado de http://www.jbc.org/content/276/43/40071.full.pdf+html Fardy, P. S., Yanowitz, F. G., & Wilson, P. K. (1988). Cardiac Rehabilitation, Adult Fitness, and Exercise Testing (2da. ed., p. 303). Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. Ford, E. S., Kohl, H. W. Mokdad, A. H., Ajani, U. A. (2005). Sedentary behavior, physical activity, and the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. Obesity Research, 13(3), 608-614. Ford, E. S., Schulze, M. B., Kröger, J., Pischon, T., Bergmann, M. M., & Boeing H. (2010). Television watching and incident diabetes: Findings from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam Study. Journal of Diabetes, 2(1),23-27. doi:10.1111/j.1753-0407.2009.00047.x. Recuperado de http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1753-0407.2009.00047.x/pdf Foster, J. A., Gore, S. A., & West, D. S. (2006). Altering TV viewing habits: an unexplored strategy for adult obesity intervention? American Journal of Health Behavior, 30(1), 3-14. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.30.1.1. Franklin, (2009). (pp. 53-54). Gade, W., Schmit, J., Collns, M., & Gade, J. (2010). Beyond obesity: the diagnosis and pathophysiology of metabolic syndrome. Clinical Laboratory Science, 23(1), 51-61. Recuperado de http://gi-group-2010.wikispaces.com/file/view/Beyond+Obesity+The+Diagnosis+and+Pathophysiology+of+Metobolic+Syndrome.pdf Gallagher, P. J. (2013). Chapter 1: Homeostasis and cellular signaling. En R. A. Rhoades, & D. R. Bell (Eds.), Medical physiology: Principles for clinical Medicine (4ta. ed.; pp.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business. Gambetta, V. (2007). Athletic Development The Art & Science of Functional Sports Conditioning (p. 72-77). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Garber, C. E., Blissmer, B.,

Deschenes, M. R., Franklin, B. A., Lamonte, M. J., Lee, I. M., Nieman, D. C., &

Swain, D. P. (2011). Quantity and Quality of Exercise for Developing and

Maintaining Cardiorespiratory, Musculoskeletal, and Neuromotor Fitness in

Apparently Healthy Adults: Guidance for Prescribing Exercise. Medicine &

Science in Sports & Exercise, 43(7), 1334-1359.

doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb. Recuperado de Gardiner, P. A., Healy, G. N., Eakin, E. G., Clark, B. K., Dunstan, D. W., Shaw, J. E., Zimmet, P. Z., & Owen, N. (2011). Associations Between Television Viewing Time and Overall Sitting Time with the Metabolic Syndrome in Older Men and Women: The Australian Diabetes Obesity and Lifestyle Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(5), 788-796. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03390.x. Recuperado de la bases de datos de EBSCOhost (CINAHL with Full Text). Garrett, R. H., & Grisham, C. M. (2013). Biochemistry (5ta. ed., p. 758). Boston, MA: Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning. Goldberg, I. J., Le, N. A., Ginsberg, H. N.,

Krauss, R M., & Lindgren, F. T. (1988). Lipoprotein metabolism during acute

inhibition of lipoprotein lipase in the cynomolgus monkey. Journal of

Clinical Investigation, 81(2), 561–568. doi:10.1172/JCI113354. Gore, S. A., Foster, J. A., DiLillo, V. G., Kirk, K., & West, D. S. (2003). Television viewing and snacking. Eating Behaviors, 4(4), 399–405. Recuperado de http://www.bat.uoi.gr/files/animal_physiology/2010_list_projects/01.pdf Gordon, E., Golanty, E., & Browm, K. M. (1999). Health and Wellness (6ta. ed., p. 6). Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. Gordon, N. F., & Mitchell, B. S. (1993). Health appraisal in the nonmedical setting. En J. L. Durstine, A. C., King, P. L., Painter, J. L., Roitman, L. D., Zwiren & W. L. Kenney (Eds.), ACSM's Resource manual for guidelines for exercise testing and prescription (2da., ed., pp. 219-228). Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger. Gortmaker, S. L., Must, A., Sobol, A. M., Peterson, K., Colditz, G. A., & Dietz, W. H. (1996). Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986-1990. Archive of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine, 150(4),56-62. Gupta, M. K. (2013). Glycemic biomarkers as tools for diagnosis and monitoring of diabetes. Medical Laboratory Observer, 45(3), 8-12. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (CINAHL with Full Text). Hahn, D. B., & Payne, W. A. (1999). Focus on Health (4ta. ed., p. 3). Boston: WCB/McGraw-Hill. Hamburg, N. M., McMackin, C. J., Huang, A. L., Shenouda, S. M., Widlansky, M. E., Schulz, E., Gokce, N., Ruderman, N. B, Keaney, J. F. Jr., & Vita, J. A. (2007). Physical inactivity rapidly induces insulin resistance and microvascular dysfunction in healthy volunteers. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 27(12), 2650-2656. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153288. Recuperado de http://atvb.ahajournals.org/content/27/12/2650.full.pdf+html Hamilton, M. T., Areiqat, E., Hamilton, D. G., & Bey, L. (2001). Plasma triglyceride metabolism in humans and rats during aging and physical inactivity. International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 11(Suppl), S97-S104. Hamilton, M. T., Hamilton, D. G., Zderic, T. W. (2007). Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes, 56(11), 2655-2667. Recuperado de http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/56/11/2655.full.pdf+html Hamilton, M. T., Healy, G. N.,

Dunstan, D. W., Zderic, T. W., & Owen, N. (2008). Too little exercise and too

much sitting: Inactivity physiology and the need for new recommendations on

sedentary behavior. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports, 2(4),

292-298. doi:10.1007/s12170-008-0054-8. Recuperado de Hardman, A. E., & Stensel, D. J. (2009). Physical activity and health: The evidence explained (2da. ed., pp. 14, 279-280, 293). New York: Routledge Taylor & Francias Group. Harrison, K, & Marske, A. L. (2005).

Nutritional content of foods advertised during the television programs children

watch most. American Journal of Public Health, 95(9), 1568–1574.

doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.048058. Recuperado de

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1449399/ Haskell, W. L., Lee, I. M., Pate, R. R, Powell, K. E., Blair, S. N., Franklin, B. A., Macera, C. A., Heath, G. W., Thompson, P. D., & Bauman, A. (2007). Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation, 116(9), 1081-1093. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185649. Recuperado de http://www.natap.org/2011/newsUpdates/Circulation-2007-ACSM_AHA Recommendations-1081-93.pdf Healy, G. N., Matthews, C. E., Dunstan, D. W., Winkler, E. A., & Owen, N. (2011). Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003–06. European Heart Journal. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451. Recuperado de http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2011/01/08/eurheartj.ehq451.full.pdf+html Healy, G. N., Dunstan, D. W., Salmon, J., Cerin, E., Shaw, J. E., Zimmet, P. Z., & Owen, N. (2007). Objectively measured light-intensity physical activity is independently associated with 2-h plasma glucose. Diabetes Care, 30(6), 1384-1389. Recuperado de http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/30/6/1384.full.pdf+html Healy, G. N., Dunstan, D. W., Salmon, J., Cerin, E., Shaw, J. E., Zimmet, P. Z., & Owen N. (2008). Breaks in sedentary time: beneficial associations with metabolic risk. Diabetes Care, 31(4), 661-666. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2046. Recuperado de http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/31/4/661.full.pdf+html Healy, G. N., Dunstan, D. W.,

Salmon, J., Shaw, J. E., Zimmet, P. Z., & Owen N.(2008). Television time and

continuous metabolic risk in physically active adults. Medicine & Science

in Sports & Exercise, 40(4), 639-645. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181607421.

Recuperado de Healy, G. N., Wijndaele, K.,

Dunstan, D. W., Shaw, J. E., Salmon, J., Zimmet, P. Z., & Owen N. (2008).

Objectively measured sedentary time, physical activity, and metabolic risk: the

Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab). Diabetes Care,

31(2), 369-371. Recuperado de Henderson, H. E., Kastelein, J. J., Zwinderman, A. H., Gagné, E., Jukema, J. W., Reymer, P. W., Groenemeyer, B. E., Lie, K. I., Bruschke, A. V., Hayden, M. R., & Jansen, H. (1999). Lipoprotein lipase activity is decreased in a large cohort of patients with coronary artery disease and is associated with changes in lipids and lipoproteins. Journal of Lipid Research, 40(4), 735-743. Recuperado de http://www.jlr.org/content/40/4/735.full.pdf+html Henson J., Yates, T., Biddle, S. J.,

Edwardson, C. L, Khunti, K., Wilmot, E. G., Gray, L. J., Gorely, T., Nimmo, M.

A, & Davies M. J. (2013). Associations of objectively measured sedentary

behaviour and physical activity with markers of cardiometabolic health.

Diabetologia. doi:10.1007/s00125-013-2845-9. Herd, S. L., Kiens, B., Boobis, L. H., & Hardman, A. E. (2001). Moderate exercise, postprandial lipemia, and skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase activity. Metabolism, 50(7), 756-762. Heyward, V. H. (1998). Advanced fitness assessment & exercise prescription (3ra. ed., p. 2). Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics Books. Higashida Hirose, B. Y. (1991). Ciencias de la salud (2da. ed., pp. 1-3, 6, 47-51, 269-270). México: McGraw-Hill Interamericana. Homans, J. (1954). Thrombosis of the deep leg

veins due to prolonged sitting. New England Journal of Medicine, 250(4),

148-149. Hu, F. B. (2003). Sedentary lifestyle and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Lipids, 38(2), 103-108. Hu, F. B., Leitzmann, M. F., Stampfer, M. J., Colditz, G. A., Willett, W. C., & Rimm, E. B. (2001). Physical activity and television watching in relation to risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus in men. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161(12), 1542-1548. Recuperado de http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=648479 Hu, F. B., Li, T. Y., Colditz, G.

A., Willett, W. C., & Manson, J. E. (2003). Television watching and other

sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus

in women. The Journal of the American Medical Asociation, 289(14),

1785-1791. Recuperado de Hu, G., Qiao, Q., Tuomilehto, J., Eliasson, M., Feskens, E. J., & Pyörälä, K. (2004). Plasma insulin and cardiovascular mortality in non-diabetic European men and women: a meta-analysis of data from eleven prospective studies. Diabetologia, 47(7), 1245-1256. Institute of Medicine (2005). Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (macronutrientes). Washington, DC: National Academy of Press. Recuperado de http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?isbn=0309085373 Instituto de Estadísticas de Puerto Rico (2010). Nuevas Estadísticas de Mortalidad, 2000-08. San Juan, Puerto Rico. Recuperado de http://www.salud.gov.pr/Datos/EstadisticasVitales/Informe%20Anual/Nuevas%20Estad%C3%ADsticas%20de%20Mortalidad.pdf Institute for Research and Education HealthSystem Minnesota. (1996). The activity pyramid: A new easy-to-follo physical activity guide to help you get fit & stay healthy [Brochure]. Park Nicollet HealthSource (No. HE 169C). Inzucchi, S. E., & Sherwin, R. S. (2012). Type 2 diabetes mellitus. En L. Goldman, & A. I. Schaver (Eds.), Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed., pp. e237-2 - e237-3). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Saunders Jakes, R. W., Day, N. E., Khaw, K. T., Luben, R., Oakes, S., Welch, A., Bingham, S., Wareham, N. J. (2003). Television viewing and low participation in vigorous recreation are independently associated with obesity and markers of cardiovascular disease risk: EPIC-Norfolk population-based study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 57(9), 1089-1096. Recuperado de http://www.nature.com/ejcn/journal/v57/n9/pdf/1601648a.pdf Jensen, M. D. (2012). Obesity. En L. Goldman, & A. I. Schaver (Eds.), Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed., p. 1409). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Saunders Jonas, S & Phillips, E. M. Phillips (Eds.) (2009). ACSM's Exercise is Medicine™: A Clinician's Guide to Exercise Prescription (pp. vii-viii)Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Katzmarzyk, P. T., Church, T., Craig, C., & Bouchard, C. (2009). Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 41(5), 998-1005. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b014e3181930355. Recuperado de http://www.ergotron.com/portals/0/literature/other/english/ACSM_SittingTime.pdf Kaptoge, S., Di Angelantonio, E., Lowe, G., Pepys, M. B., Thompson, S. G., Collins, R., & Danesh, J. (2010). C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet, 375(9709), 132-140. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61717-7. Recuperado de http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3162187/?report=printable Kent, M. (1994). The Oxford dictionary of sports science and medicine (pp. 169, 286). New York: Oxford University Press. Kriska, A. M., & Caspersen, C. J. (1997). A collection of physical activity questionaires for health related research. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 29(6 Supp.), S1-205. Komurcu-Bayrak, E., Onat, A., Poda, M., Humphries, S. E., Acharya, J., Hergenc, G., Coban, N., Can, G., & Erginel-Unaltuna, N. (2007). The S447X variant of lipoprotein lipase gene is associated with metabolic syndrome and lipid levels among Turks. Clinical Chimica Acta, 383(1-2), 110-115. Recuperado de http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0009898107002884 Lank, N. H., Vickery, C. E., Cotugna, N., & Shade, D. D. (1992). Food commercials during television soap operas: what is the nutrition message? Journal of Community Health, 17(6), 377-384. Lee, I-Min, & Paffenbarger, Jr., R. S. (1996). How much physical activity is optimal for health? Methodological considerations. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 67(2), 206-208. Leutholtz, B. C., & Ripoll, I. (1999). Exercise and Disease Management (p. 3). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Levine, J. A. (2004). Nonexercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT): environment and biology. American Journal of Physiology and Endocrinology Metabolism, 286(5), E675-E685.doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00562.2003. Recuperado de http://ajpendo.physiology.org/content/286/5/E675.full.pdf+html Levine, J. A., Eberhardt, N. L., & Jensen, M.

D. (1999). Role of nonexercise activity thermogenesis in resistance to fat gain

in humans. Science, 283(5399), 212-214.

doi:10.1126/science.283.5399.212. Levine, J. A., & Kotz, C. M. (2005). NEAT – non-exercise activity thermogenesis – egocentric & geocentric environmental factors vs. biological regulation. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 184(4), 309-318. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (Academic Search Premier) Levine, J. A., Lanningham-Foster, L. M., McCrady, S. K., Krizan, A. C., Olson, L. R., Kane, P. H., Jensen, M. D., & Clark, M. M. (2005). Interindividual variation in posture allocation: possible role in human obesity. Science, 307(5709), 584-586. doi:10.1126/science.1106561. Recuperado de la Base de datos de Infotrac (Academic OneFile). Lopategui Corsino, E. (2006a). Bienestar y calidad de vida (pp. 4, 11-12, 22-24, 44, 65, 76, 78, 501-504, 521-522). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. Lopategui Corsino, E. (2006b). Experiencias de laboratorio: Bienestar y calidad de vida (pp. 139-144). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. Lopategui Corsino, E. (1997). El ser humano y la salud (7ma. ed., pp. 2-9). Hato Rey, Puerto Rico: Publicaciones Puertorriqueñas. Maron, B. J., Araújo, C. G., Thompson, P. D., Fletcher, G. F., de Luna, A. B., Fleg, J. L., Pelliccia, A., Balady, G. J., Furlanello, F., Van Camp, S. P., Elosua, R., Chaitman, B. R., Bazzarre, T. L. (2001). Recommendations for preparticipation screening and the assessment of cardiovascular disease in masters athletes: an advisory for healthcare professionals from the working groups of the World Heart Federation, the International Federation of Sports Medicine, and the American Heart Association Committee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention. Circulation, 103(2), 327-334. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.103.2.327. Recuperado de http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/103/2/327.full.pdf+html Maron, B. J., Thompson, P. D., Puffer, J. C., McGrew, C. A., Strong, W. B., Douglas, P. S., Clark, L. T., Mitten, M. J., Crawford, M. H., Atkins, D. L., Driscoll, D. J., & Epstein, A. E. (1996). Cardiovascular preparticipation screening of competitive athletes. A statement for health professionals from the Sudden Death Committee (clinical cardiology) and Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee (cardiovascular disease in the young), American Heart Association. Circulation, 94(4), 850-856. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.94.4.850. Recuperado de http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/94/4/850.long Martínez-González, M. A., Martínez, J. A., Hu, F. B., Gibney, M. J., & Kearney, J. (1999). Physical inactivity, sedentary lifestyle and obesity in the European Union. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 23(11), 1192-1201. McArdle, W. D., Katch, F. I., & Katch, V. I. (2013). Sports and Exercise Nutrition (4ta. ed., pp. 204-205). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. McCulloch, J. (2002). Health risks associated with prolonged standing. Work, 19(2), 201-205. Recuperado de la Base de datos de EBSCOhost (CINAHL with Full Text). McGinnis, M. J., Williams-Russo, P.,

& Knickman, J. R. (2002). The case for more active policy attention to health

promotion. Health Affairs, 21(2),78–93. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78. Recuperado

de

http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/21/2/78.full.html Miller, A. L., Grais, I. M., Winslow, E., & Kaminsky, L. A. (1991). The definition of physical fitness. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 31(4), 639-640. Miranda, P. J., DeFronzo, R. A., Califf, R. M., & Guyton, J. R. (2005). Metabolic syndrome: definition, pathophysiology, and mechanisms. American Heart Journal, 149(1), 33-45. Moore, G. E., Roberts, S. O., & Durstine, J. L. (2009). Introduction. En J. L. Durstine, G. E. Moore, P. L. Painter, & S. O. Roberts (Eds.). ACSM's Exercise management for persons with chronic diseases and disabilities (3ra. ed., pp. 3-8). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, Inc. Moore, G. E., Painter, P. L., Lyerly, G. W., & Durstine, J. L. (2009). Managing exercise in persons with multiple chronic conditions. En J. L. Durstine, G. E. Moore, P. L. Painter, & S. O. Roberts (Eds.). ACSM's Exercise management for persons with chronic diseases and disabilities (3ra. ed., pp. 31-37). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, Inc. Morales Bedoya, A (s.f.). Historia natural de la enfermedad y niveles de prevención (Definición de conceptos). Puerto Rico: Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Ciencias Médicas, Escuela de Salud Pública. Recuperado de http://www.rcm.upr.edu/PublicHealth/medu6500/Unidad_1/Rodriguez_Historia-natural-Prevencion.pdf Morales Bedoya, A. (1985-1986). Tasas, razones, próporciones. En Lecturas Curso INTD-4005: Salud: Una Perspectiva Integral (pp. 4-7). Tomo I, II, año Académico 1985-86. Puerto Rico: Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto de Ciencias Médicas, Escuela de Salud Pública. Morales, R. S., & Ribeiro, J. O. (2006). Heart diseases. En Exercise in Rehabilitation Medicine (2da. ed., pp. 117-129). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, Inc Murrow, E. J., & Oglesby, F. M. (1996) Acute and chronic illness: similarities, differences and challenges. Orthopaedic Nursing, 15(5), 47-51. Naide, M. (1957). Prolonged television viewing as cause of venous and arterial thrombosis in legs. Journal of the American Medical Association, 165(6), 681-682. National Cholesterol Education Program [NCEP] (2001). Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). The Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(19), 2486-2497. doi:10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. Recuperado de http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=193847 National Heart Foundation of Australia (2011). Sitting less for adults. Recuperado de http://www.heartfoundation.org.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/HW-PA-SittingLess-Adults.pdf Nelson, M. E., Rejeski, W. J.,

Blair, S. N., Duncan, P. W., Judge, J. O., King, A. C., Macera, C. A., &

Castaneda-Sceppa, C. (2007). Physical activity and public Health in older

adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the

American Heart Association. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise,

39(8), 1435–1445. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3180616aa2. Recuperado de Nielsen Television Audience 2010 &

2011 (p. 15). Nieman, D. C. (2007). Exercise Testing and Prescription: A health-related approach (6ta. ed., pp. 33. 779). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. Nieman, D. C. (1986). The Sports Medicine Fitness Course (pp. 32-37, 210-211). Palo Alto, CA: Bull Publishing Company. NIH Consensus Development Panel on Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health. (1996). Physical activity and cardiovascular health. Journal of the American Medical Association, 276(3), 241-246. Olivieri, F., et al. (1982). Cátedra de Medicina Preventiva y Social (pp. 16-21, 265). Argentina: Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires. Olsen, L. K., Reducan, K. J., & Baffi, C. R. (1986). Health Today (2da. ed., p. 2). New York: MacMillan Publishing Company. Owen, N, Bauman, A., & Brown, W. (2009). Too much sitting: a novel and important predictor of chronic disease risk? British Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(2), 81-83. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.055269. Recuperado de http://bjsm.bmj.com/content/43/2/81.full.pdf+html Owen, N, Healy, G. N., Matthews, C. E, & Dunstan, D. W. (2010). Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 38(3), 105-113. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2. Recuperado de http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3404815/ Owen, N, Leslie, E., Salmon, J., & Fotheringham, M. J. (2000). Environmental determinants of physical activity and sedentary behavior. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 28(4), 153-158. Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Paffenbarger, Jr., R. S., Hyde, R. T., & Wing, A. L. (1990). Physical activity and fitness as determinants of health and longevity. En C. Bouchard, R. J. Shephard, T. Stephens, J. R. Sutton, & B. D. Mcpherson (Eds.), Exercise fitness, and health: A consensus of current knowledge (pp. 33-48). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books. Page, P. (2005). Functional flexibility activities for older adults. Functional U, 3(1), 1-4. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (SPORTDiscus with Full Text). Painter, P. (2008). Exercise in

Chronic Disease: Physiological Research Needed. En P. M.

Clarkson, (Ed.), Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 36(2), 83-90. Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e318168edef. Paisley, T. S., Joy, E. A., Price, R. J. Jr. (2003). Exercise during pregnancy: A practical approach. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 2(6), 325–330. Pate, R. R., O’neill, J. R., &

Lobelo, F. (2008). The evolving definition of ‘‘sedentary’’.

En P. M. Clarkson, (Ed.), Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 36(4), 173-178. Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams &

Wilkins. doi:10.1097/JES.0b013e3181877d1a. Pate, R. R., Pratt, M., Blair, S.

N., Haskell, W. L., Macera, C. A., Bouchard, C., Buchner, D., Ettinger, W.,

Heath, G. W., King, A. C., Andrea Kriska, A., Leon, A. S., Marcus, B. H.,

Morris, J., Paffenbarger, R. S., Patrick, K., Pollock, M. L., Rippe, J. M.,

Sallis, J., & Wilmore, J. H. (1995). Physical activity and public health. A

recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the

American College of Sports Medicine [Abstract]. Journal of the American

Medical Association, 273(5), 402-407. Recuperado de

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7823386 Patton, R. W., Corry, J. M., Gettman, L. R., & Graf, J. S. (1986). Implementing health/fitness programs (p. 21). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc. Plowman, S. A., & Smith, D. L. (2011). Exercise Physiology for Health, Fitness, and Performance (p. 220). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Pollock, M. L., Graves, J. E., Swart, D. L., & Lowenthal, D. T. (1994). Exercise training and prescription for the elderly. Southern Medical Journal, 87(5), S88-S95. Pollock, M. L., Wilmore, J. H., & Fox III, S. M. (1990). Exercise in health and disease: Evaluation and prescription for prevention and rehabilitation (2da ed., pp. 100-110, 371-484). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunder Company. Porta, M. (2008). Dictionary of Epidemiology (5ta. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press for the International Epidemiology Association. Prakash, V. V., Hariohm, K. K., Vijayakumar, P. P., & Bindiya, D. (2012). Functional Training in the Management of Chronic Facial Paralysis. Physical Therapy, 92, 605-613. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (SPORTDiscus with Full Text). President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports (1971). Physical Fitness Research Digest, Series 1(1), Washington, DC: President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. Pronk, N. (2010). The problem with too much sitting: A workplace conundrum. ACSM'S Health & Fitness Journal, 15(1), 41-43. doi: 10.1249/FIT.0b013e318201d199. Recuperado de http://journals.lww.com/acsm-healthfitness/Fulltext/2011/01000/The_Problem_With_Too_Much_Sitting__A_Workplace.14.aspx Pronk, N. P., Katz, A. A., Lowry,

M., & Payfer, J. R. (2012). Reducing occupational sitting time and improving

worker health: The Take-a-Stand Project, 2011. Preventing Chronic Disease:

Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy, Vol. 9. doi: Proper, K. I., Cerin, E., Brown, W. J., & Owen, N. (2007). Sitting time and socio-economic differences in overweight and obesity. International Journal of Obesity, 31(1), 169–176. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803357. Recuperado de http://www.nature.com/ijo/journal/v31/n1/pdf/0803357a.pdf Public Health Agency of Canada (1998). Canada's physical activity guide for healthy active living. Ottawa, Ontario (Canada): Public Health Agency of Canada. Recuperado de http://www.physicalactivityplan.org/resources/CPAG.pdf Rahl, R. L. (2010). Physical activity and health guidelines: Recommendations for various ages, fitness levels, and conditions from 57 authoritative sources (pp. 15-41). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Ransdell, L. B., Dinger, M. K., Huberty, J., & Miller, K. H. (2009). Developing effective physical activity programs (pp. 4-8). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Roberts, C. K., & Barnard, R. James (2005). Effects of exercise and diet on chronic disease. Journal of Applied Physiology, 98(1), 3-30. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00852.2004. Recuperado de http://www.jappl.org/content/98/1/3.full Robinson, T. N. (1999). Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(16), 1561-1567. Recuperado de http://data.edupax.org/precede/public/Assets/divers/documentation//4_defi/4_015_SMART_Obesity.pdf Roitman, J. L., & LaFontain, T. (2012). The exercise professional's guide to optimizing health: Strategies for preventing and reducing chronic disease (pp. 1-2). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Roy, B. A. (2012). Fitness focus copy-and-share: Sit less and stand and move more. ACSM'S Health & Fitness Journal, 16(2), 4. doi: 10.1249/01.FIT.0000413046.15742.a0. Recuperado de http://journals.lww.com/acsm-healthfitness/Fulltext/2012/02000/Fitness_Focus_Copy_and_Share__Sit_Less_and_Stand.4.aspx Rutten, G. M., Savelberg, H. H., Biddle, S. J. H., & Kremers, S. P. J. (2013). Interrupting long periods of sitting: good STUFF. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1). doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-1. Recuperado de http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/pdf/1479-5868-10-1.pdf Saikia, A., Oyamaa, T., Endoa, K., Ebisunoa,

M., Ohiraa, M., Koidea, N., Muranob, T., Miyashitaa, Y., & Shiraic, K. (2007).

Preheparin serum lipoprotein lipase mass might be a biomarker of metabolic

syndrome. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 76(1), 93–101. Salmon, J., Bauman, A., Crawford, D., Timperio, A., & Owen, N. (2000).The association between television viewing and overweight among Australian adults participating in varying levels of leisure-time physical activity. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders, 24(5), 600-606. Salmon, J., Owen, N., Crawford, D., Bauman, A., & Sallis, J. F. (2003). Physical activity and sedentary behavior: a population-based study of barriers, enjoyment, and preference. Health Psychology, 22(2), 178-88. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.2.178 Sandvik, L., Erikssen, J., Thaulow, E., Erikssen, G., Mundal, R., & Kaare, R. (1993). Physical Fitness as a Predictor of Mortality among Healthy, Middle-Aged Norwegian Men. The New England Journal of Medicine, 328(8), 533-537. Recuperado de http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/328/8/533. Santiago, L. E., & Rosa, R. (2007). Elementos de la diversidad cultural. Optar por la diversidad cultural: El gran desafío del momento actual. En R. Rosa Soberal (Ed.), La Diversidad cultural: Reflexión crítica desde un acercamiento interdisciplinario (pp. 1-11). Hato Rey, PR: Publicaciones Puertorriqueñas, Inc. Saunders, T. J., Tremblay, M. S.,

Després, J., Bouchard, C., Tremblay, A., & Chaput, J. (2013). Sedentary

behaviour, visceral fat accumulation and cardiometabolic risk in adults: A

6-year longitudinal study from the Quebec Family Study. Plos ONE, 8(1),

1-8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054225. Scott, S. (2006). Exercise during pregnancy. ACSM’s Health & Fitness Journal, 10(2), 37-39. Recuperado de http://exerciseismedicine.org/pdfs/c36pregnancy.pdf Seaward, B. L. (2006). Essential of managing Stress (pp. 17-18). Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. Sedentary Behaviour Research Network (2012). Letter to the editor: standardized use of the terms "sedentary" and "sedentary behaviours". Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 37(3), 540-542. doi: 10.1139/h2012-024. Recuperado de http://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/h2012-024 Semenkovich, C. F. (2012). Disorders of lipid metabolism. En L. Goldman, & A. I. Schaver (Eds.), Goldman's Cecil Medicine (24th ed., p. 1348). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Saunders. Shephard, R. J. (1995). Physical activity, fitness, and health. Quest, 47(3), 288-303. Shephard, R. J. (2007). Responses of brain, liver, kidney, and other organs and tissues to regular physical activity. En C. Bouchard, S. N. Blair, & W. L. Haskell (Eds.), Physical Activity and Health (pp. 127-140). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Shephard, R. J., Thomas, S., & Weller, I. (1991). The Canadian Home Fitness Test. 1991 update. Sports Medicine, 11(6), 358-366. Shimada, M., Ishibashi, S., Gotoda, T., Kawamura, M., Yamamoto, K., Inaba, T., Harada, K., Ohsuga, J., Perrey, S., Yazaki, Y., & Yamada, N. (1995). Overexpression of human lipoprotein lipase protects diabetic transgenic mice from diabetic hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 15(10), 1688-1694. Recuperado de http://atvb.ahajournals.org/content/15/10/1688.long Simpson, K. (1940). Shelter deaths from pulmonary embolism. Lancet, 14(), 774. s. a. (2006). Impact of physical activity

during pregnancy and postpartum on chronic disease risk. Medicine and

Science in Sports and Exercise, 38(5), 989-1006. Recuperado de

http://www.acsm.org/docs/publications/Impact%20of%20Physical%20Activity%20during%20 Sipe, C., & Ritchie, D. (2012). The Significant 7 Principles of Functional Training for Mature Adults. IDEA Fitness Journal, 9, 42-49. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (SPORTDiscus with Full Text). Slattery, M. L. (1996). How much physical activity do we need to maintain health and prevent disease? Different disease--Different mechanism. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 67(2), 209-212. Stump, C. S., Hamilton, M. T., & Sowers, J. R. (2006). Effect of antihypertensive agents on the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 81(6), 796-806. doi:10.4065/81.6.796. Recuperado de http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025619611617345 Swain, D., & Ehrman, J. K. (2010). Exercise prescription. En American College of Sports Medicine, ACSM’s Resource Manual for Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (6ta. ed., pp.448-475, 559-559). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Swain, D. P., & Leutholtz, B. C. (2007). Exercise Prescription: A Case Study Approach to the ACSM Guidelines (pp. 6, 116-117). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, Inc. Swartz, A. M., Squires, L., & Strath, S. J. (2011). Energy expenditure of interruptions to sedentary behavior. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 8, 69.doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-69. Recuperado de http://www.ijbnpa.org/content/pdf/1479-5868-8-69.pdf Taylor, H. L. (1983). Physical activity: Is it still a risk factor? Preventive Medicine, 12, 20-24. The President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports [PCPFS] (2008). Definitions: Health, fitness, and physical activity (pp. 20, 22). Washington, DC: President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. Recuperado de https://www.presidentschallenge.org/informed/digest/docs/200003digest.pdf Thompson, W. (2010). ACSM's Resouces for the Personal Trainer (3ra. ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincoyy Williams & Wilkins. Thorp, A. A., Owen, N., Neuhaus, M., & Dunstan, D. W. (2011). Sedentary behaviors and subsequent health outcomes in adults a systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996-2011. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 41(2), 207-215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.004. Tremblay, M.S., Esliger, D.W., Tremblay, A., & Colley R. (2007). Incidental movement, lifestyle-embedded activity and sleep: new frontiers in physical activity assessment. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 98 (Suppl 2), S208-S217. Tremblay, M. S., Colley, R. C., Saunders, T. J., Healy, G. N., & Owen, N. (2010). Physiological and health implications of a sedentary lifestyle. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 35(6), 725-740. doi:10.1139/H10-079. Recuperado de http://www.sfu.ca/~leyland/Kin343%20Files/sedentary%20review%20paper.pdf Tucker, L. A., & Bagwell, M. (1991). Television viewing and obesity in adult females. American Journal of Public Health, 81(7), 908–911. Recuperado de http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1405200/pdf/amjph00207-0086.pdf Tucker, L. A., & Friedman, G. M. (1986). Television viewing and obesity in adult males. American Journal of Public Health, 79(4), 516–518. Recuperado de http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1349993/pdf/amjph00230-0116.pdf United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (1979). Healthy People: The Surgeon General's Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. DHEW (PAS) Publication No. 79-55071. Washington, DC: U.S. Goverment Printing Office. Recuperado de http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/access/NNBBGK.pdf United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (1980). Promoting Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives for the Nation. Washington, DC: US Goverment Printing Office United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (1991). Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. DHHS Publication No. (PHS) 91-50212. Washington, DC: US Goverment Printing Office United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (2000). Healthy People 2010: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. Washington, DC: US Goverment Printing Office United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (2010). Healthy People 2020: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. Washington, DC: US Goverment Printing Office. Recuperado de http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/pdfs/HP2020objectives.pdf United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS]. & Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (s. f.). Healthy People 2020: A Resource for Promoting Health and Preventing Disease Throughout the Nation [Presentación Electrónica]. Recuperado de http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/consortium/HealthyPeoplePresentation_2_24_11.ppt United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (2008). Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report, 2008 (pp. A-4, C-4, D-4). Recuperado de http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/report/pdf/CommitteeReport.pdf United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (2008). 2008 Physical activity guidelines for americans. Recuperado de http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/pdf/paguide.pdf United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] & United States Department of Agriculture [USDA] (2005). Dietary guidelines for Americans (6ta. ed). Washington, DC: U.S. Goverment Printing Office. Recuperado de http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/publications/dietaryguidelines/2005/2005dgpolicydocument.pdf United States Department of Health

and Human Services [USDHHS](1996). Physical

activity and health: A report of the surgeon general. Sudbury, MA: Jones

and Bartlett Publishers. Recuperado de

http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/sgr/pdf/sgrfull.pdf United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] (1993). 1992 National survey of worksite health promotion activities: Summary. American Journal of Health Promotion, 7(6), 452-464. Vaquero Puerta, J. L. (1982). Salud Pública (pp. 26-27). Madrid: Ediciones, S. A. Vega, G. L. (2001). Obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. American Heart Journal, 142(6), 1108-116. doi:10.1067/mhj.2001.119790. Recuperado de http://sistemas.fcm.uncu.edu.ar/medicina/pfo/04-optativos/hta/Sindr.Metabolico.Review.pdf Vioque, J., Torres, A., & Quiles, J. (2000). Time spent watching television, sleep duration and obesity in adults living in Valencia, Spain. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders, 24(12), 1683-1688. Recuperado de la base de datos de EBSCOhost (Academic Search Premier) Visich, P. S., & Fletcher, E. (2009). Myocardial infarction. En J. K. Ehrman, P. M. Gordon, P. S. Visich, & S. J. Ketteyian, (Eds.), Clinical exercise physiology (2da. ed., pp. 281-299). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Warren, T. Y., Barry, V., Hooker, S. P., Sui,

X., Church, T. S., & Blair, S. N. (2010). Sedentary behaviors increase risk of

cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Medicine and Science in Sports

and Exercise, 42(5), 879-885. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c3aa7e. Weiss, T., Kreitinger, J., Wilde, H., Wiora, C., Steege, M., Dalleck, L., & Janot, J. (2010). Effect of functional resistance training on muscular fitness outcomes in young adults. Journal of Exercise Science & Fitness, 8(2), 113-122. Recuperado de http://www.scsepf.org/doc/201012/09_JESF_2010-023.pdf Whitmer, R. W. (2009). Employee health promotion: A historical perspective. En N. P. Pronk (Ed.), ACSM’s worksite health handbook: A guide to building healthy and productive companies (2da.ed., 10-20). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. Widlansky, M. E., Gokce, N., Keaney, J. F. Jr, & Vita, J. A. (2003). The clinical implications of endothelial dysfunction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 42(7), 1149-1160. doi:10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00994-X. Recuperado de http://ac.els-cdn.com/S073510970300994X/1-s2.0-S073510970300994X-main.pdf?_tid=0a69c93c-a494-11e2-9266-00000aacb362&acdnat=1365896831_289c27df7256eef9c434984972bace56 Williams, M. A. (2001). Exercise testing in cardiac rehabilitation. Exercise prescription and beyond. Cardiology Clinics, 19(3), 415-431. Wittrup, H. H., Tybjaerg-Hansen, A., & Nordestgaard, B. G. (1999). Lipoprotein lipase mutations, plasma lipids and lipoproteins, and risk of ischemic heart disease. A meta-analysis. Circulation, 99(22):2901-2907. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.22.2901. Recuperado de http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/99/22/2901.full.pdf+html World Health Organisation [WHO] (2000). Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Recuperado de http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_894.pdf World Health Organization [WHO] (1947). Constitution of the World Health Organization. Chronicle of WHO, 1(1). Wright, D. (2012). Healthy People 2020: A Foundation for Health and Disease Prevention Throughout the Nation. Recuperado de http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/nchs2012/SS-25_WRIGHT.pdf Yanagibori, R., Kondo, K., Suzuki, Y., Kawakubo, K., Iwamoto, T., Itakura, H., Gunji, A. (1998). Effect of 20 days' bed rest on the reverse cholesterol transport system in healthy young subjects. Journal of Internal Medicine, 243(4), 307-312. Recuperado de http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00303.x/pdf Young, A. (1987). Exercise and chronic disease. En: D. Macleond, R. Maughn, M. Nimmo, T. Reilly & C. Williams (Eds.), Exercise: Benefits, Limits and Adaptations (pp. 20-32). New York: E. & F.N. SPON. Zderic, T. W., & Hamilton, M. T.

(2012). Identification of hemostatic genes expressed in human and rat leg

muscles and a novel gene (LPP1/PAP2A) suppressed during prolonged physical

inactivity (sitting). Lipids In Health & Disease, 11(1), 137-149.

doi:10.1186/1476-511X-11-137. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||